Where This Question Came From (and Why It Still Hurts)

If you’re Deaf or hard of hearing, you’ve probably heard this one: “Can you read my lips?”

It’s often asked with the same energy as “Can you read my mind?”, and to be honest, sometimes it feels just as impossible.

But this question didn’t come out of nowhere. It has a history. A not-so-great one.

The Origin Story Nobody Asked For

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, powerful educators and “speech experts” around the world began pushing the idea that Deaf people should stop signing and instead learn to speak and lipread. This “oralist” movement banned sign languages in schools and punished children for using them. Sign languages weren’t just discouraged, they were actively outlawed in classrooms.

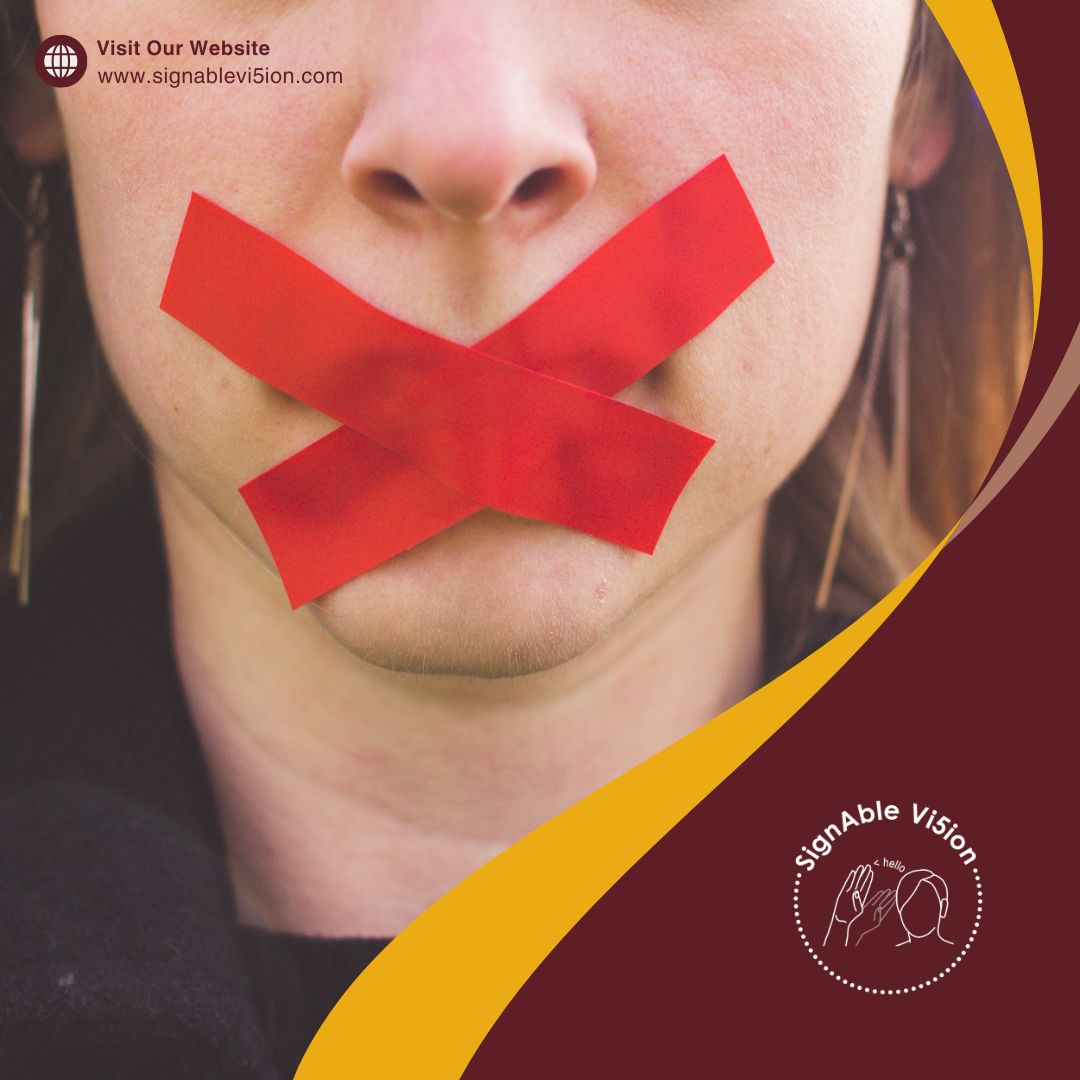

The message was clear: “If you’re Deaf, you must speak and lipread to be accepted.”

This forced generations of Deaf people to survive on a skill that even experts admitted was never 100% reliable. The attitude still lingers today. Hollywood loves to show a Deaf character perfectly lipreading across a crowded room, through a car window, or while someone’s back is turned. (We’re good, but we’re not superheroes.)

Lipreading: A Tricky, Imperfect Art

Here’s the truth: no one lipreads perfectly. Even people who are very skilled miss words, especially with new speakers or unfamiliar accents.

Lipreading is like trying to solve a puzzle with half the pieces missing, and sometimes the puzzle picture keeps changing.

Why? Because:

- People talk with their mouths full. (it’s GROSS!)

- Mustaches and beards blur mouth shapes.

- Crooked teeth or tiny lip movements hide key sounds.

- Many English sounds look identical on the lips (try “pat,” “bat,” and “mat” silently in a mirror).

And even if you know the word, you may have never seen it on the lips before. Imagine trying to lipread:

“The scone is in the sconce.”

If you’ve never seen “sconce” before, or only heard it once, long ago — you’ll be guessing.

Tools Help, But They’re Not Magic

Hearing aids and cochlear implants can sometimes fill in the missing pieces, but they’re not miracle workers. They amplify sound, but they don’t make speech clear or teach your brain words you’ve never heard.

For me personally, when I wore hearing aids, I could fill in gaps more quickly. Now, since neither a hearing aid nor a cochlear implant helps me anymore, it takes even longer to piece things together. It’s not a matter of trying harder – it’s simply how our brains and senses work.

It’s Not “One and Done”

Another myth: that if you’re a “good lipreader,” you can instantly understand anyone.

Reality: it takes time to get used to a person’s mouth patterns. The first conversation may be rocky. The second gets easier. The tenth? Maybe you’re in sync. But there’s no first-try magic button.

Why This Matters Today

Asking “Can you read my lips?” carries the weight of history. It comes from a time when society forced Deaf people to reject their own language and culture. For many of us, that question is not just about communication – it’s a reminder of being told we weren’t allowed to sign, to belong, to be ourselves.

So instead of starting with “Can you read my lips?” try:

“What’s the best way for me to communicate with you?”

It’s simple. It’s respectful. It gives the other person the lead in their own communication needs.

Final Thought (With a Wink)

Lipreading can be a helpful tool. But it’s not a magic trick, a universal skill, or a substitute for sign language.

We’re not superheroes from the movies. We’re people, navigating a world that sometimes talks with its mouth full.